When Krishna Narayanan was four years old, his mother showed him an apple and repeated, “Apple… apple…” He knew not only the word ‘apple’, but many, many other complicated words. He wanted to cry out to his mother that he knew all of them, but no words came out of his mouth; just a garbled sound.

Inside an elevator as a four year old, Krishna felt extremely tense. To relieve the tension, he stretched out his right hand and watched his fingers. This was a weird mannerism to the onlookers, and many thought he was insane. The liftman ridiculed him with nasty jokes. It hurt Krishna, and he badly wanted to tell his mom that he felt ridiculed and hurt, but he lived in a silent world.

Once on the school playground a kid came and asked, ‘How are you?’ Krishna answered in his mind, ‘Fine, how are you?’ But in reality, nothing came out of his mouth.

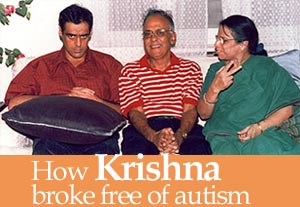

He had to pass through 23 long years of mental torture, hurt, and agony, but his mother’s relentless spirit in educating him and Ayurvedic treatment at the Kottakkal Arya Vaidya Sala and at the K A Samajam Hospital at Shoranur helped Krishna write what went on within him.

He wrote: ‘Who was I to the world? But really, who was I? The world and the autistic are like the theatre audience and the actor. The world sees the autistic as weird and insane… Kindled by tension, fear and insecurity, the autistic behaves inappropriately. The weird behaviour of the autistic drives the world up the wall. The state of the autistic is a sad one.’

BOSTON, December 1971. When Krishna was born, Jalaja Narayanan was in bliss. At that moment itself she had so many dreams for him. “I wanted him to be a great scientist. I wanted him to be a neurosurgeon. At times, I thought both.”

But soon the young mother found her dreams crumbling. Even as a one year old, her son didn’t walk, didn’t utter a word, didn’t show any interest in toys, and didn’t like to be held or cuddled. By two, he was displaying bizarre behaviour like looking at his hands, flapping them, rocking, hitting his head against the wall, tapping his chin, screaming, throwing tantrums and showing extreme fear in front of strangers. Krishna wanted to be far away from people all the time, in the isolation of his room; he even refused to come to the living room.

“He was that withdrawn and lonely,” remembers Jalaja. “I had another child Malini [now chief of neurosurgery at Harvard Medical Hospital in Boston] two years elder to him. So I knew there was something wrong with this child. But those were the Seventies, and there was nothing available on autism. The doctors didn’t know how to diagnose autism, even in the US.”

So, when she took the year-and-a-half-old Krishna to the doctor, he was diagnosed to be deaf. The doctor also told her that Krishna would never be able to hear any sound. “That was the first diagnosis,” says Jalaja, “but I didn’t believe her because I had noticed him turning when the telephone rang, but not when we called him.”

At four, at the Children’s Hospital in Boston, Krishna was diagnosed as severely autistic. The doctor also told her that he would never understand the human voice.

Thus began the young mother’s long drawn war on autism.

“I was all alone with the diagnosis, and I didn’t know what it was,” she recounts. “When the doctors said my child would never understand human speech, I told them, no, I will make him understand. They asked, how? I said, I have 24 hours a day. They said, you cannot overbake a cake. I said, don’t say that about my child, my child is a living being. He’s not a cake.”

Krishna writes, ‘Riding on my horse — my young and innocent mom — I fought a relentless, tireless, epochal war. The kid in me was handcuffed and life was hideous. I was a total prisoner of autism.’

Krishna heard every word that was uttered; he also understood what was happening around him. ‘To my parents, I was not dumb. In reality, I was never dumb. I knew the alphabet, I knew many words, and I knew how to fashion sentences. The tragedy of autism is being unable to communicate in words. An autistic’s mind is normal, even brilliant, but complete absence of verbal expression makes his behaviour totally misunderstood. To the world, I was weird and insane, given to funny movements with no speech. To me, I was normal in intelligence, feelings and emotions, but afflicted with a debilitating disease that robbed me of speech and coordination, and endowed me with enormous tension and fear,’ Krishna wrote at age 24.

He describes his life as a human drama, a Greek tragedy that is seemingly sad and hopeless. He also likes to call his story a ‘positive story of struggle, survival and success against all odds’.

ON JUNE 24, P S Ramamohan Rao, governor of Tamil Nadu, inaugurated The Autism Centre started by Jalaja Narayanan in Chennai. The idea of starting such a centre came up when parents bombarded Jalaja for advice on how to bring up an autistic child. “I have been spending all my free time counselling parents, one at a time, which was taking a toll on me. So, I decided to start a centre from where I can counsel many parents because parents need motivation. This is not a one-day fight; it is a life-long war.”

She also has plans to start an Indian society for autism so that all parents of autistic children, all professionals working on autism, and all schools with autistic children are integrated.

On the same day, the governor released a book jointly written by the mother and son, titled, Quest, Search for Quality Life. It comes after two books written separately by Jalaja and Krishna. Jalaja Narayanan wrote From A Mother’s Heart; A journal of survival, challenge and hope in which she described her traumatic life bringing up an autistic child and also the various techniques used to overcome autism. The techniques are scattered through the book.

Krishna’s first book, Wasted Talent; Musings of an Autistic, was an account of how he got over all the hurdles to finally open his mind to his parents. Soon, he was writing his autobiography and learning complicated mathematics and physics.

When many parents of autistic children constantly asked for advice on the various techniques and therapies used by them, the mother and son decided to write a book jointly.

It starts with the chapter, ‘Dream a Quality Life’ for an autistic child. Krishna says the parents should ask every day, ‘How can I improve my child today?’

What helped Krishna come out of the tension-filled days in the early years of his life was music. His mother, a Carnatic singer herself, sensed her child’s ear for music. With music in the background, Krishna who rocked and whined all night started sleeping soundly. Music also calmed him a lot more.

The second chapter talks about the ‘Power of Intuition’. Jalaja was so convinced that the child had the ability to understand and learn that she kept teaching him and reading out Charles Dickens, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Jane Austen, etc though there was absolutely no response from him. She continued to read out to him and make him listen to audio tapes of great world literature because she saw a ‘sparkle’ in his eyes.

Krishna wrote in his book, ‘She felt sparkling eyes cannot come from a dull mind. This was a bold hypothesis when there was precious little output from me. In a similar vein, parents must probe and think where the strength of the child lies. Where does it show interest or aptitude? What activity calms him or what activity he does not mind doing? Earlier this talent is detected, larger will be the benefits.’

Education is a necessity, Jalaja felt strongly, though to educate an autistic is extremely tough. Krishna admits, ‘No challenge is greater than the challenge to educate the autistic because they are restless and their rigidity and rituals interfere with learning. They can neither write nor talk.’

But what gave Krishna’s life a breakthrough was ayurveda. ‘We stumbled upon Ayurvedam and it totally turned my life around. Without it, I will not be where I am today. I cannot emphasize enough the wonderful role Ayurvedic treatment had in my life.’

Once the treatment calmed his body and mind, his body became less rigid, fingers became supple, and he slowly started writing. By then, years had passed, and he was 23.

His father, Dr S Narayanan, took a break from his job as director of Lucent Technologies, Bell Laboratories, USA, and started teaching Krishna simultaneous equations in algebra. Krishna picked it up quickly. His father then taught him calculus, which also Krishna grasped rapidly. Dr Narayanan then moved to differential equations and Newtonian physics. Krishna loved quantum physics and relativity.

‘What did I get from education?’ he wrote. ‘Primarily, it provided me with self-confidence. Even though an autistic, I am as intelligent as the normal person, if not better, and can understand subtle and tough concepts in mathematics and physics.’

As he acquired the ability to write, his parents asked him to tell them about himself so that they could know him. Words slowly came out onto paper, and there he was at the age of 23 telling his parents who he was, what he felt at age four, how he felt humiliated and ridiculed because the world looked at him as weird and insane when he had an intelligent mind. His mother was so impressed with his writing that she wanted him to write a book on himself.

‘This is more easily said than done; thus started an odyssey of six long years. Everyday, slowly, ever so slowly, I wrote a couple of paragraphs and the book began to take shape.’

When Krishna titled the book Wasted Talent, his mother objected. ‘The title reflects ultimately my belief that the talent of an autistic is wasted away if it is not nurtured.’ An adamant Krishna refused to change the title.

The book was published in July 2003, to rave reviews. Now, Krishna is in the process of writing a novel.

He ends the book with, ‘What is my future? I really don’t know, but I can dream.’ He dreams of learning more mathematics and teaching young students. ‘That may happen because of the advances in the Internet. I could teach without speech.’

He also dreams of the US Congress allocating enough funds to research both Eastern and Western treatments for autism. His third dream is that the world will not abandon him to an institution when his parents move on.

His final dream is, ‘An angel would descend from heaven to marry me and give me happiness and a family.’